The Many Shades of Rainbow Capitalism

As more companies embrace a gay-friendly marketing push, questions arise about intent and authenticity

By Anna-Liza Badaloo

There was a time when a rainbow flag on a business door was a powerful political statement. It meant that queer folks were welcome and could shop in safety. These days, it’s more likely to signal that Pride Month is underway.

Every June, brands drape themselves in rainbows. But come July 1, the rainbow decor is often packed away, not to reappear until June of the following year. This is just one example of shallow marketing to the queer community, otherwise known as rainbow capitalism.

Is there a pot of gold for the queer community at the end of this capitalist rainbow? Or is this mere ‘rainbowwashing,’ with no substantive action towards LGBTQ+ equity to back it up?

Colin Druhan, executive director of Pride at Work Canada, describes rainbow capitalism as “all the sizzle without the steak.” Many brands have ramped up gay representation in ad campaigns, but often there is no clear relevance to queer community issues. “There is absolutely no relationship to the queer community, or efforts to understand or address the challenges that queer people face,” says Druhan. “All these efforts are very visual.”

Evan Vipond, PhD candidate at York University’s School of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies, points to the framing of the LGBTQ+ community as a consumer demographic as a key signifier of rainbow capitalism. “It’s really about this recognition that the queer community is in fact a consumer community and that they have purchasing power,” notes Vipond.

The most obvious manifestation of rainbow capitalism is June-only queer marketing. “Clearly attached [to this] is the idea of Pride Month as a time for queer people to consume,” says Vipond. “[But] what about the other 11 months of the year when LGBTQ+ folks are less visible, and not being told to celebrate who they are?”

Conflicting messaging from companies that own multiple brands is a more subtle sign of rainbow capitalism, as some of these companies may appeal to both queer and anti-queer audiences. “That’s where neoliberalism comes in,” explains Vipond. “These decisions are being made based on cost-benefit analysis. The political aspect is seen as secondary to economics. This is why we see tension sometimes in what is being presented.”

Then there are those brands that advertise that they donate a portion of proceeds to an LGBTQ+ organization. Ticking off the social credibility box in this manner is great for optics, but, as Druhan points out, “consumers shouldn’t have to buy things as a prerequisite for companies to support queer causes and equity. That’s not support, that’s promotion.”

WHO BENEFITS?

There are clear optics and profit advantages to companies engaging in rainbow capitalism. But are there any benefits to the LGBTQ+ community? Queer business owner Kim Alke of home and lifestyle goods store Spruce Toronto has mixed feelings. “On the one hand, I love to see it,” says Alke. “Especially growing up in the 1980s during the AIDS crisis and not having positive recognition for those of us in the community. But it’s really crossing over into performative allyship.”

Vipond encourages a deeper dive into the benefits question.“Is the LGBT+ community benefiting more than it’s being hindered?” they ask. “Is the community being centred? Is the point to directly improve the lives of LGBTQ+ people?” Unfortunately, the most marginalized members of the queer community (such as trans and/or BIPOC folks) tend not to benefit from this new brand of queer-friendly capitalism. “If much of the visibility is two middle-class gay dads with an adopted child, that may do something for those who are being reflected. Middleclass men typically have more disposable income; they are now seen as respectable,” explains Vipond. “But what about queer and trans sex workers, and those with disabilities – are they being represented? [Or] is the representation further marginalizing other parts of the community?”

Many companies continue to play it safe, featuring only LGBTQ+ representation that will ruffle the fewest feathers. In many cases, they are slow to diversify their queer-facing ad campaigns, viewing it as dangerous to their bottom line. “Brands may think it’s too risky to provide visibility to other members of the community because of these respectability politics,” notes Vipond.

AUTHENTICITY

Sartaj Sarkaria, chief diversity officer and vice president, corporate services, at the Canadian Marketing Association, notes that brands need to begin changing their strategy to better reflect true diversity. To start, they can do this by acknowledging that they don’t know everything. “Lead with curiosity, and keep an open mind and ear,” Sarkaria suggests, adding that this mindset sets the stage for marketers to ask the right questions. “Brands need to ask ‘Who makes up your community? What does your day-to-day look like? How can we be meaningful to you?’”

Spruce Toronto’s Alke previously worked in the corporate sector, where she was often the only queer person on the campaign team. She minces no words about the lack of understanding of gay issues that she saw in some corporate teams spearheading rainbow marketing. “The people creating the [marketing] campaigns were clueless about our community and the issues we face,” Alke recalls.

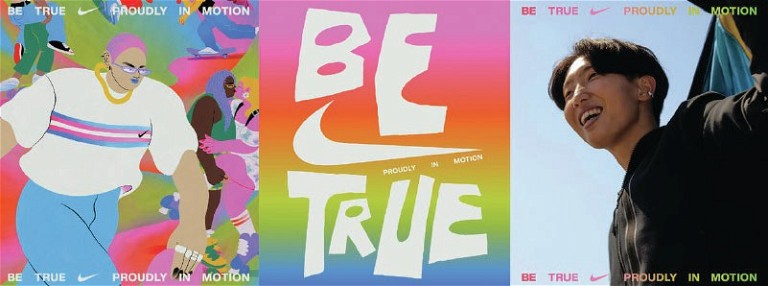

Rainbow colours have become an important part of marketing campaigns for brands across the globe

It’s generally understood that tapping into the lived experience of LGBTQ+ employees can inform truly authentic marketing campaigns. But if those queer employees are a mainly heterogenous, privileged group, brands are still not getting the full picture. They need to seek it out.

Druhan is very aware that Pride at Work Canada’s 11 employees don’t represent the full spectrum of LGBTQ+ diversity. The key is assessing which voices are missing, he says, and actively seeking out those views. “Not getting all perspectives means that you can pave over the needs of people,” he notes, explaining that partnerships are the perfect way for brands to access the expertise they lack. “It benefits everyone to partner with organizations who truly understand the community’s issues and how to best address them. Ask partner organizations what they think should go into the ad or campaign.”

An authentic commitment to advance LGBTQ+ equity needs to go far beyond colourful ad campaigns. It needs to be embedded in the work culture, and the products and services on offer. Many of Canada’s major banks have LGBTQ-facing marketing campaigns, for instance, but are they putting their customer service policies where their money is? “A lot of queer and trans people have expressed that when they actually deal with these banks as individual consumers, they experience transphobia or homophobia,” says Vipond. Name changes and voice authentication in phone banking are two key issues that can prove challenging for trans people.

Customer interactions can also be teachable moments for the public. Alke notes that “we work really hard to keep our language non-gendered. We’ve had tough conversations about girls’ versus boys’ toys and how to reference someone when you don’t know how they identify. These interactions open up new conversations, which we welcome.”

Rainbow capitalism can be obvious or subtle. Ultimately, it’s about whether brands are genuinely walking their LGBTQ+ equity talk. While some queer inclusion is better than none, we must not gloss over what kind of inclusion is being offered to whom, and the potential impact on the most vulnerable members of the community. ■